Crash, Burn, Breathe

Or: What I Did On My Summer Vacation

First of all, I want to say thank you and welcome to all the new subscribers! Most of you are probably here because of the sticker sale, which was such a joyful experience, and I’ll be writing more about that soon. Today, though, I’m tackling some heavier topics. September is Suicide Prevention Month. Those who have been reading for a while know that I’m a suicide loss survivor. Many may not know that I am also an attempt survivor. This post will discuss suicidal ideation and chronic illness, but will not do so graphically. Still, please read with care. If you or a loved one are experiencing suicidal thoughts or grief, please check out NAMI’s crisis guide here, and the 988 support guide here. Also, please know that no matter how you feel right now, you are not alone.

Some of you may remember that I took the month of August off. I had a lot of Big Plans. I was going to keep writing and turn the month’s unposted essays into a zine. I was going to go to San Francisco to celebrate my 25th wedding anniversary, see the Ruth Asawa exhibition at SFMOMA, eat at a few fancy restaurants, and take some (hopefully gorgeous) polaroids that weren’t of my yard for a change. I was going to work on some art projects and read some books and hang with my kids and soak up the remaining days of summer.

Instead, I crashed.

For those who don’t already know, life with chronic illness and dynamic disability is full of ups and downs. There are days, sometimes weeks even, where I feel *almost* normal. Then there are episodes of increased symptoms (usually after a specific event that demanded too much from my cooked spaghetti body) that last a few days or weeks. I call those flares. Flares are annoying, but manageable.

A crash is what happens when you keep pushing after a flare. While a flare usually involves one or two symptoms acting up at a time, a crash is everything, everywhere, all at once. Headache, brain fog, GI symptoms, muscle aches, nerve pain, weakness, hypotension, fatigue. It’s a full life derailment, and usually lasts at least a month. (This one has been close to six weeks, assuming I’m actually coming out of it *fingers crossed*).

Despite the instantaneous sound of the term, my recent crash happened slowly, over the first two weeks of August. When it became clear that this was more than a flare, I canceled my trip. I spent the rest of the month housebound, mostly bedbound. I wrote almost nothing, save for a few fragments in my Notes app. I read nothing. I drew nothing. I watched nothing. I maintained a shred of sanity by taking photographs of the sky from the landing of my stairwell. A sliver of time, a square of something huge and open, just beyond my reach.

You would think—given that I’ve been going through this particular head/neck pain cycle for the last year, given the many, many other chronic illness cycles I’ve experienced over the last 15 years—that I’d be able to take comfort in the certainty that I would survive this latest setback.

But, unfortunately, that isn’t how this works at all.

In Buddhism, there’s a concept called The Second Arrow, which Thich Nhat Hahn explains much better than I do:

“[I]f an arrow hits you, you will feel pain in that part of your body where the arrow hit; and then if a second arrow comes and strikes exactly at the same spot, the pain will not be only double, it will become at least ten times more intense. The unwelcome things that sometimes happen in life—being rejected, losing a valuable object, failing a test, getting injured in an accident—are analogous to the first arrow. They cause some pain. The second arrow, fired by our own selves, is our reaction, our storyline, and our anxiety. All these things magnify the suffering.”

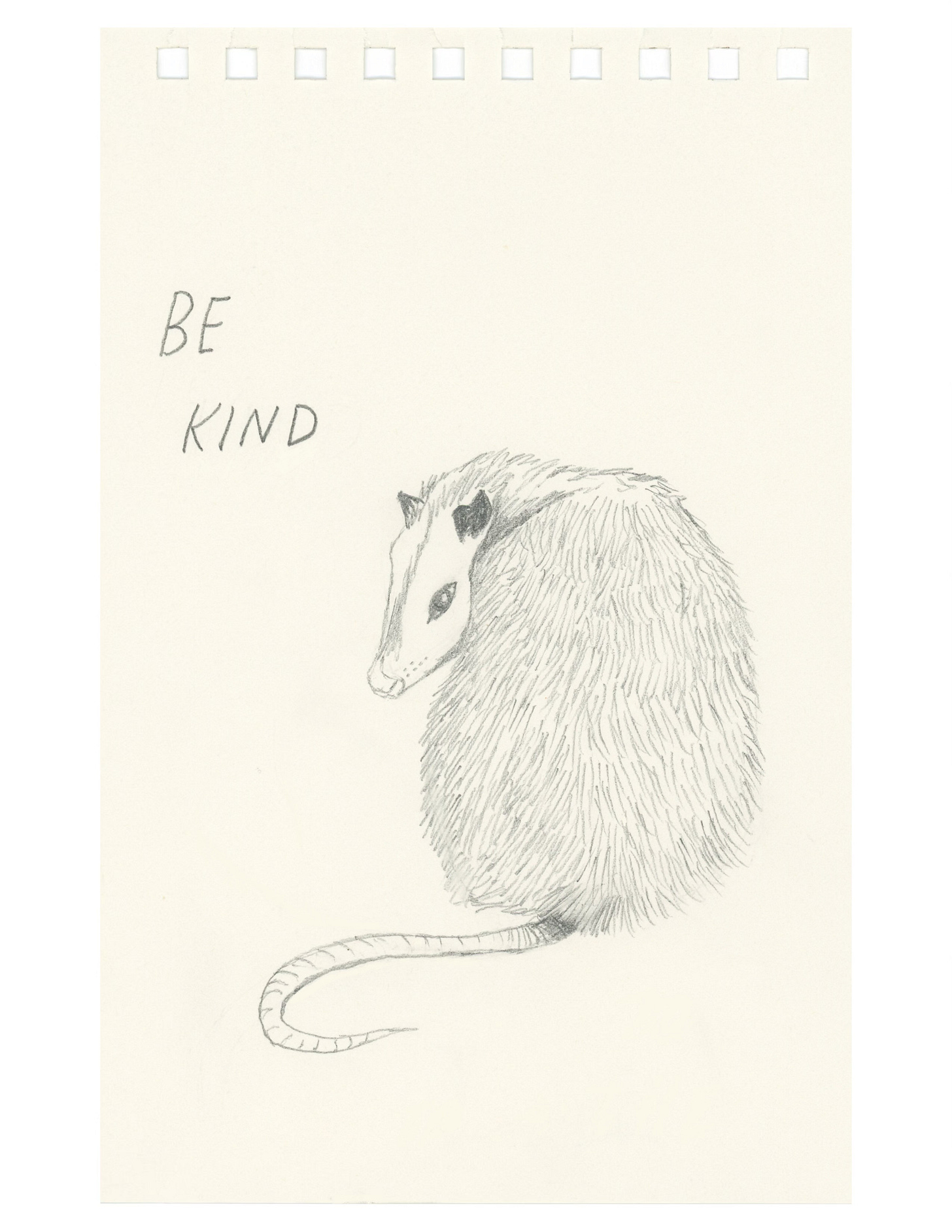

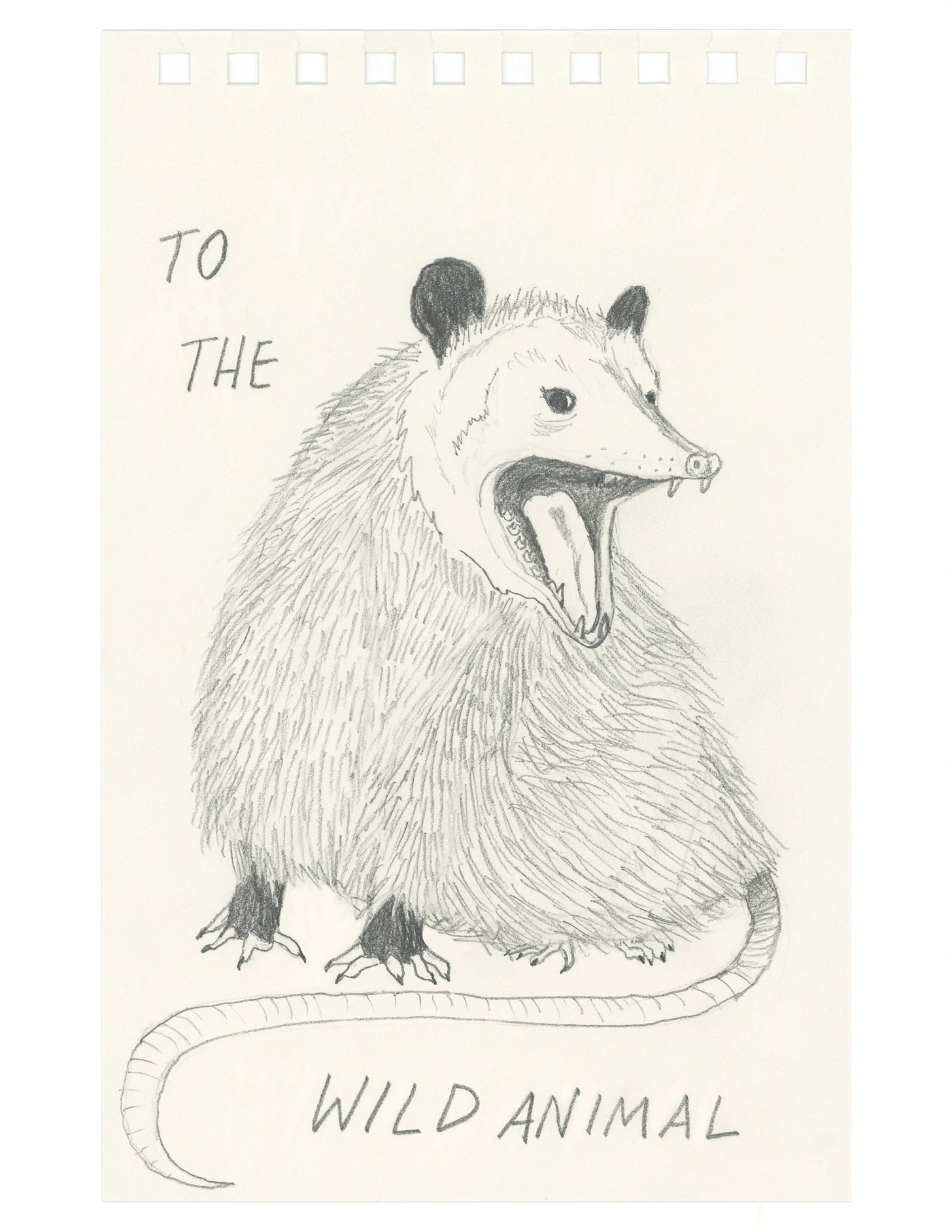

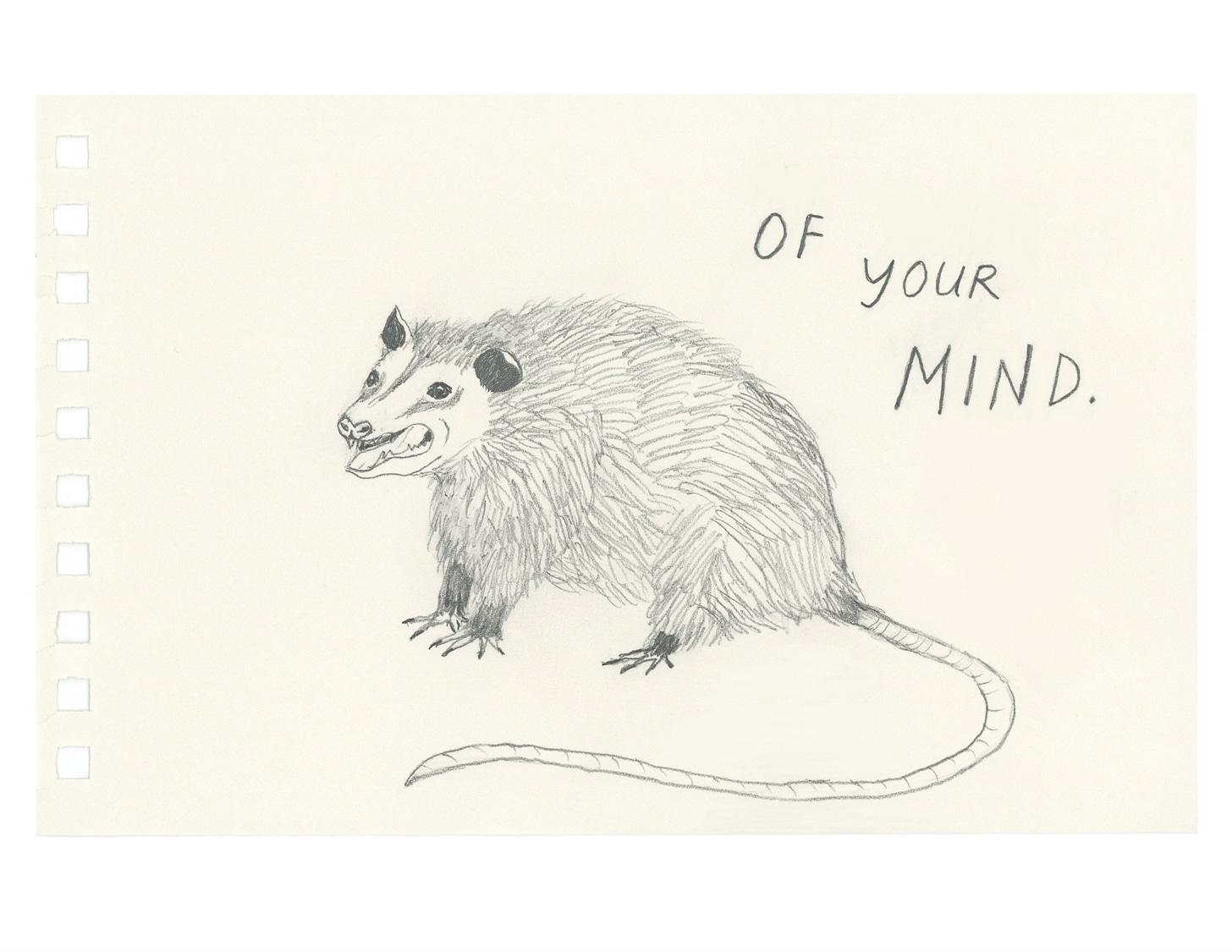

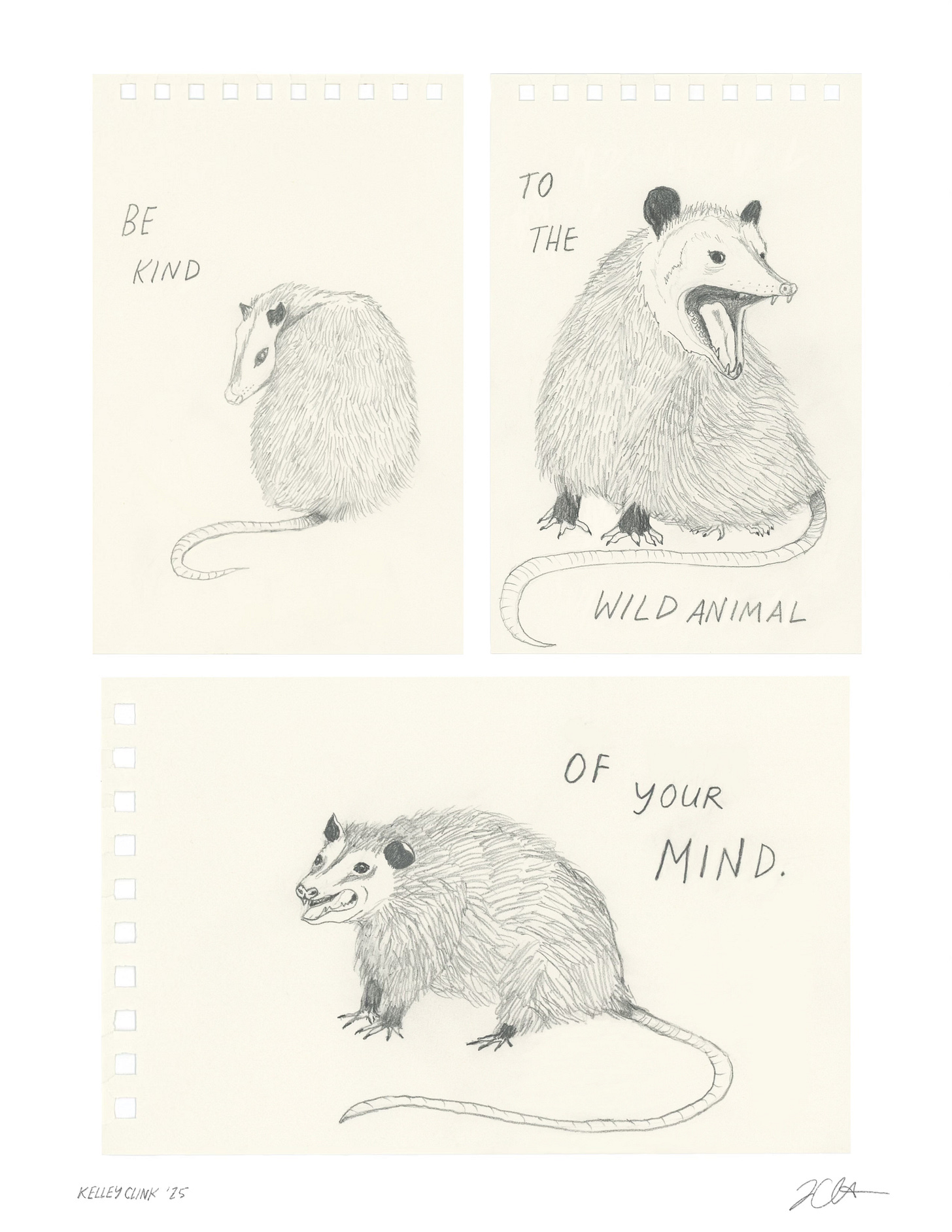

Or, as I wrote in one of my Notes app fragments: “This would all be fine, if it weren’t for the matted, rabid animal of my mind.”

This is maybe the part where I need to give you a little background. Like I mentioned in the first paragraph, I’m a suicide attempt survivor. If you’d like more details, I’ve written extensively about it here. The short version is that a lot of bad shit happened to me the year I turned 15. I tried to muddle through, because that seemed like my only option. I had no frame of reference for mental health support (it was 1994). My parents were young—a decade younger than I am now. They had no frame of reference, either. I ended up feeling so exhausted, so overwhelmed, so lonely and hopeless that I tried to end my life.

Like many attempt survivors, I regretted my attempt almost immediately. I didn’t want to die, and was glad that I survived. That was thirty years ago this October. I’ve never attempted again.

And yet, not a year has gone by where I haven’t experienced at least a moment, however small or fleeting, of wanting to end my life.

In the years after my brother’s death, my own suicidality (which had been mostly absent since my attempt) came rushing back like a flash flood. I wasn’t going to act on it, had firmly and irrevocably decided that I would never act on it, but I carried it around with me like a diving bell, festooned with the barbed wire of my grief.

I read a lot of books about suicide during that time. I read books by survivors and books by clinicians. Twenty years have passed since then, and kids and chronic illness have pushed a lot of information out of my brain. Still, I seem to remember that a lot of studies about suicidality involved neuroplasticity. I remember, in those years, picturing my own suicidal ideation as an actual path in my mind, cut through an overgrown forest. I understood that I’d taken that route so many times that it had become automatic, a reflex; faster and far easier than trying to bushwack my way to something new.

That understanding alone was helpful. These thoughts I had weren’t my fault. I didn’t have them because I was a bad, ungrateful person. I didn’t have them because I was selfish, or I didn’t love the people I loved. There was just a shortcut in wilderness of my brain.

This didn’t change the fact that I didn’t want it to be there.

Regardless of why my suicidal thoughts happened, they were scary. They made me feel worse. I hated them, which kind of made me hate myself.

This carried on for years, quietly, mostly privately, until the sudden onset of my illness. I was in unrelenting pain, unable to eat and rapidly losing a dangerous amount of weight. No health care provider seemed to know why, or what would happen next, and I was terrified, exhausted, and despondent. Months dragged on. Recovery seemed hopeless. Survival was questionable. Suicidal thoughts were loud. Finally, one blindingly bright afternoon, I told a friend1 about them. It was maybe the first time I’d told anyone, outside of a family member or therapist, that I felt like I wanted to die.

She looked at me very tenderly and said: “Do you really wish you were dead? Or do you just wish things were different?”

According to the Buddha, desire and attachment are the roots of suffering. They are also a completely natural part of being human. The goal isn’t to erase them, it’s simply to recognize them for what they are. Just in doing that alone we experience some ease. And in that moment with my friend, for the first time in my life, I saw what the shortcut in my mind really was: a desire for my circumstances to change.

That was over fifteen years ago. And yet, as I mentioned above, the reflex to pepper myself with second arrows hasn’t lessened in the least.

Thankfully, my understanding of it has changed.

This year I’ve been trying really hard to learn to love the soft animal of my body. I’m now realizing that this latest crash has been an opportunity to extend that gentleness and acceptance to the wild animal of my mind.

Living in a sick and hurting body is hard. Feelings of helplessness spawn feelings of hopelessness. It doesn’t matter, in the moment, that I’ve been here a dozen times before and gotten through it. Pain obliterates the past and future, pinning you to the present like a ethylized insect. That’s not a great place from which to think logically. My brain, bless her, is actually trying to help. The more often I can remember that, the easier it is to be compassionate with my thoughts. Dispassionate, even. I can give them a little space. A little room to breathe.

I don’t know how quickly I’ll remember any of this the next time I crash. Hopefully a little quicker than this time, but maybe not. I don’t expect I’ll ever evolve beyond shooting second arrows, but I guess that isn’t really the point. The point is to notice them, and once the intensity fades enough, to clean the wound.

I’ve been working on this essay for weeks, wondering if I should share it at all. I worry that I’m making this sound simple, or easy, when it’s neither. I worry that you’ll think that I think I’ve got it all figured out, when I definitely don’t. But I know I’m not the only one out there dealing with this, so it felt important to say something, even if it’s awkward and fumbling and still feels like the beginning of a potential understanding, rather than the end of one.

Disclaimer time! I’m not a mental health professional, or an expert on suicidal ideation. I’m a person with lived experience, and this is what I’m sharing here. If you have resources or thoughts to add, please do! I’m always looking to learn, and the first to admit that I don’t have all the answers. I don’t even have a lot of them. I have a couple, at best. And they’re more like suggestions.

This was an extra-extra soft one to write and to share, so thanks for reading. I hope you’ll be gentle with yourselves during this change of season, and that if you’re one of the many who suffer from the loss of light, that you’re able to be kind to your mind as we head into darker days.

All my love,

Kell

Shout out to Lisa!!!

Be kind to the wild animal of your mind INDEED. I feel the tenderness of this post. It’s amazingly heartwarming to me that taking photos of the sky was a balm. Brava for finding light in the very dark, and for this beautiful exploration of the second arrow. (Damn those second arrows!! May they be plucked one by one from the soft and giving fur.) 💞💞

Second shout out to Lisa.