What's in a Name?

why (extra) soft animal?

Mary Oliver’s poem Wild Geese begins like this:

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

I was maybe thirty years old the first time I read this. I related real hard to the knee-walking, having been raised by a very strict Catholic. I thought about pilgrims in Fatima, and the buzz and ache in my own knees every Sunday mass of my childhood. In Mary’s absolution, I felt both the metaphorical and the physical release of standing. What a relief to be told, finally, that I could get up.

But I skated over the next lines completely. Because even at thirty, on the precipice of the first (maybe worst) flare of my EDS, I couldn’t.

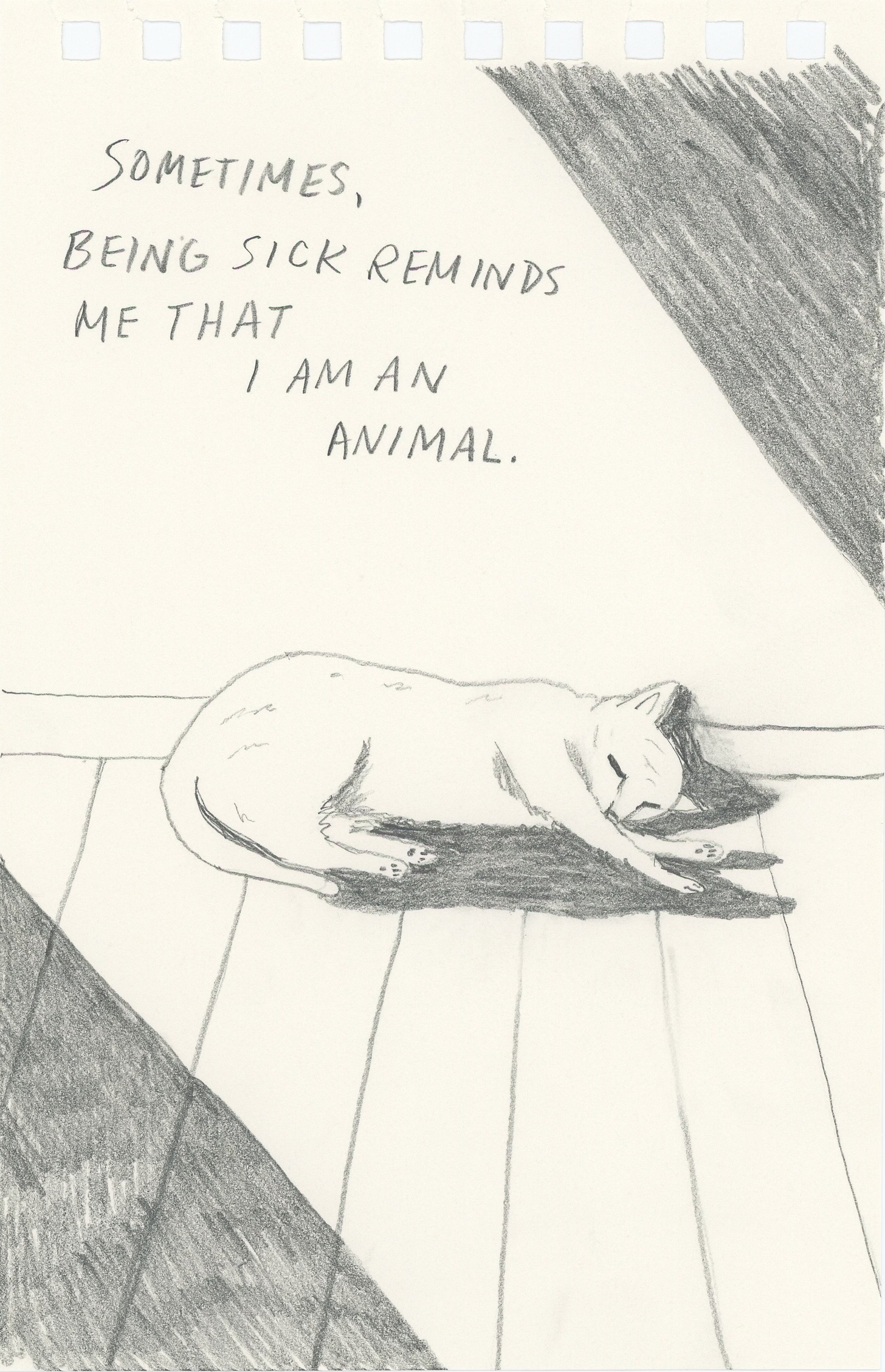

I’ve never liked thinking about my body. As a kid, the idea of having a body, of being a body, terrified me. If I thought about blood and muscles and nerves, my hands and feet went numb and my airway shrank down to the width of a needle. I knew even then that bodies were fragile, temporary, outside of our control. I was happy to ignore mine as often as I could.

Which unfortunately wasn’t as often as I would have liked. I was a scrawny kid, perpetually underweight, prone to illnesses and aches and pains. I was also anxious and highly sensitive, likely to burst into tears over small slights or frustrations. The advice I most frequently got from the adults in my life was to Toughen Up.

I understand now that the grownups were trying to teach me that life wasn’t easy, not for anyone, that I’d need to find a way to weather its storms. I actually think this is sound advice. Unfortunately the 1980s phrasing left a lot to be desired. No one talked about how validating feelings should be part of that process. No one talked about flexibility, adaptability, or acceptance. For sure no one talked about the gift of a big, soft heart. Because no one said much at all, really, beyond those two words—toughen up. And so I was left to conclude that I must be weak, that toughness was the opposite of who I currently was. I took it to mean I needed to care less. To feel less. And then, maybe, I would hurt less.

I tried. Really, I did. But my head and heart remained tender. Raw. I didn’t even get better at hiding it.

I did, however, start playing sports.

I figured if I couldn’t harden myself mentally or spiritually, I could at least be physically tough. And let me tell you, I was a beast. Despite being small, I was fast and ruthlessly competitive. I was coordinated. I loved the feeling of blowing by a competitor, pushing my body to the limit, knocking someone over, gasping for breath. I wore bruises like badges of honor. I learned to equate pain with gain. I didn’t notice that I was the only one who came to freshman basketball practice with their ankles taped. Never thought twice about the fact that I had to put sacks of frozen peas in my shin guards after soccer games. I didn’t think about the soft animal of my body. I was too busy trying not to think about the over-softness of my heart.

When I look back, I can see how my body tried to tell me how unhappy they were. The signs started in my teens and continued throughout my 20s: stress fractures, sprains, tendonitis, joint instability. Unexplained rashes, gastrointestinal distress, cycles of viral infections that just wouldn’t quit. But the more my body fought back, the harder I pushed. Exercise and activity, I reasoned, were the only things that quieted my mind, which I was still mistaking for my spirit. And after all, wasn’t that what my body was for? A vehicle, a vessel to serve the unbearably soft animal of my consciousness.

Until it couldn’t be, anymore.

It was then, in my early thirties, when my body threatened to quit altogether, when I could no longer physically outrun the softness of my heart, I started the lifelong work of learning to love my tender spirit.

And yet, while I’ve been chronically ill and disabled for about fifteen years, while I have half a dozen of Mary Oliver’s books and a graduate degree in literature, it’s only been in the last year that I really saw the third line of “Wild Geese.”

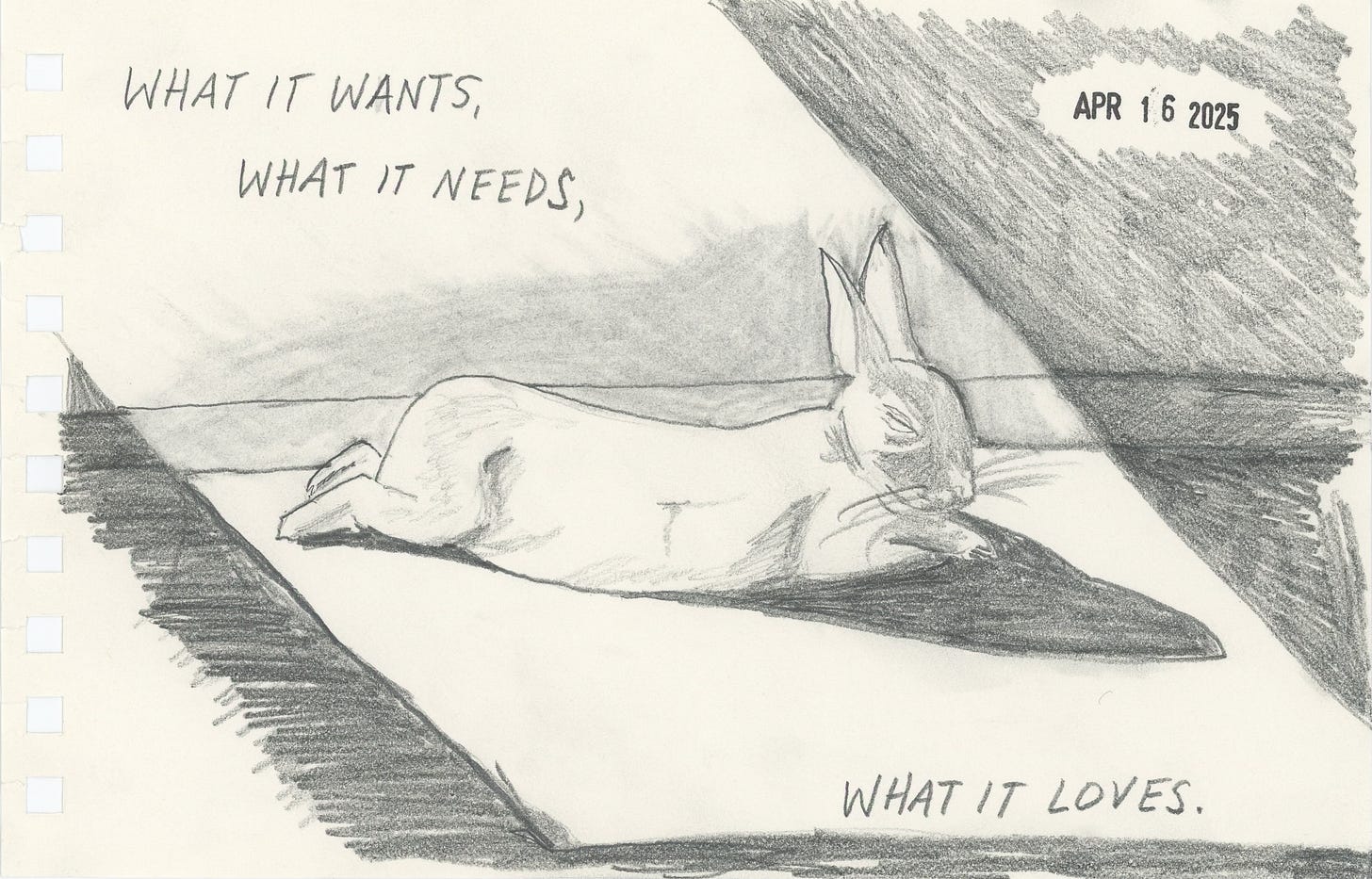

Let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.

When it finally hit me, it landed like a lightning strike. I had never, not once in all these years of pain and illness, stopped to think about what my body actually loved. When I tried to, I found I didn’t even know. Couldn’t come up with a single thing.

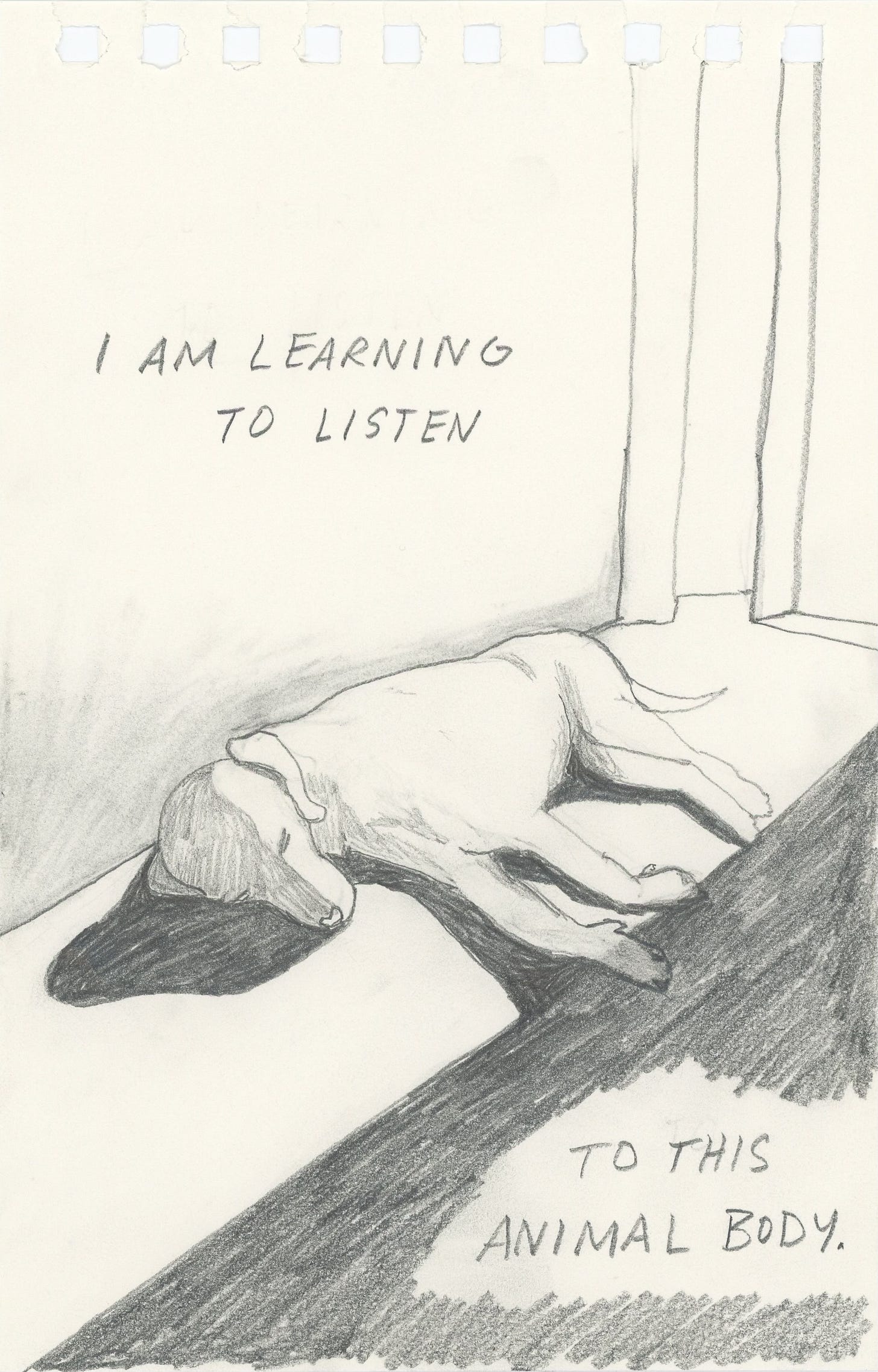

I’ve spent the last few months turning that line over and over in my mind. Really trying, for the first time in my life, to listen to my body. Here’s what I’ve discovered, so far:

My body loves direct sunlight (but burns easily, so sunscreen and breaks in the shade, please). My body loves soft breezes and birdsong. My body loves floating in Lake Michigan, and any old community swimming pool. My body loves gentle stretching (not yoga, jesus. Yoga is the fucking worst for this body), strategically placed pillows, and elastic waistbands. My body loves head and neck support. My body loves lying on a blanket in the grass. My body loves touching trees. My body loves simple, nourishing food, adequate hydration, and this thing. My body loves compression, sometimes, and sometimes clothing that is very loose. My body sometimes loves heavy blankets, and always a white noise machine. My body loves sunglasses, and quiet, and the sound and warmth of a fireplace.

I don’t know if listening to my body is going to change anything about the way it functions. I think it’s more important that that isn’t the reason I’m doing it. My body is deserving of love, no matter what it is or isn’t capable of. And so am I.

Here’s the rest of Mary’s poem, if you’d like to read it.

Also, in a clunky, non-lyrical way that I couldn’t fit in above, two of the hallmarks of EDS are unusually soft skin and difficulty building muscle. As a middle-aged person who has birthed two humans and has lost significant mobility, I’m quite literally soft. Like biscuit dough oozing from the can. Like a swirl of Dairy Queen about to slide off the cone. My youngest sinks her fingers into my upper arms. Squishy, she cries with delight. You’re so squishy! And I smile, because in her eyes, and maybe mine, too, soft is an okay thing to be.

Finally: May is Ehlers-Danlos Awareness Month. (It’s also Mental Health Awareness Month. The Venn diagram of my disabilities is getting dangerously close to a circle.) For those who are interested, I was diagnosed three years ago with type 3 Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, also known as Hypermobile EDS or hEDS. It took me TWELVE YEARS to get diagnosed, despite nearly a decade of asking doctors if hEDS could be a potential explanation for my health challenges. This is, unfortunately, not at all uncommon (especially for female presenting patients). Thankfully connective tissue disease is becoming more widely recognized and studied in the medical community. If you are interested in learning more about EDS, I highly recommend subscribing to Life and Science with Cortney Gensemer, PhD

Thanks so much for reading my softness manifesto! If this essay spoke to you, please consider liking, commenting, and/or restacking. And please tell me: what does the soft animal of your body love? I’m looking to expand my list.

Thank you for this post! My body loves my heating pad, the sound of a breeze in tree leaves, and the smell of blooming lilacs and crab apple trees.