Prairie Peace

no time for kings here, but plenty of love for monarchs

On Saturday, while millions of people marched in protest, I sat in my garden. It’s been almost ten years since I’ve been able to physically attend a protest, and I was really sad to miss this one. A huge, heartfelt thank you to everyone who attended: the photos and stories were a much needed boost.

While my abilities have changed over the years, I have continued to participate in activism in ways that are accessible to me. I write postcards and letters to voters, call my reps, and donate money. And recently I’ve started looking at the way I live my life, as a chronically ill person in a disabled body, as a form of protest.

Like many people with my condition/s, I was, once-upon-a-time, a striver. I graduated with my BA in three years, with honors, and worked while doing it.* I never had less than two jobs during my time in graduate school. One semester I had three. And I did it all while maintaining a near-perfect GPA and a bursting social calendar.

I need to point out that I didn’t do any of this with grace or ease. I had frequent episodes of overwhelm so severe that I’d sink to the bathroom floor and cry for hours, my brain as stuck as a skipped record. It never occurred to me that this was because the expectations I’d placed on myself were unreasonable. That the myth I’d been taught—that my work was my worth—was not only false, but actively harmful. No, I believed that I was the problem. I was weak, broken. Despite all I’d done, despite all I was doing, I was not enough. I would never be enough. And so I limped on. I graduated again. I worked two part-time jobs. I started to plan for a second master’s program.

Then my brother died.

After a few weeks of mourning, after helping my parents collect my brother’s belongings, after the wake and the funeral and the burial, I tried to step back into my old life—but it was gone.

Sure, the jobs were still there, but I could no longer do them. My friends were still there, but I could barely stand to see them. They were all reminders of Before. A world that no longer existed. A person I would never be again.

It should have come as no surprise that the tidal wave of grief demolished the shaky scaffolding I’d used to build my life. I’d spent the last ten years, from the time I was 15-25, attempting to outrun several adverse childhood experiences. I had depression, anxiety, and undiagnosed ADHD. I also had undiagnosed Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, the physical manifestations of which I ignored. I interpreted them as further evidence of my ineptitude, and pushed through them accordingly. It’s clear to me, now, that even if my brother’s death hadn’t shattered my facade, something else would have. It was always, eventually, going to come crashing down.

And yet it was 20 years before I understood and accepted this. Twenty years before I could let go of the deep, deep shame around my inability to embody America’s definition of productivity.**

I am currently capitalism’s worst nightmare. I value rest over production. Most of my labor (caring for home and family, writing and making art) is unpaid***. I’m raising children who will (hopefully) believe that their worth is inherent, that all humans deserve food, housing, and healthcare regardless of their abilities. That it is our job as a society to care for each other. That money isn’t the right metric for success, and that the majority of it shouldn’t be hoarded by a scant few.

And so, because I wasn’t able to demand these rights in the streets on Saturday, I sat in a chair in my front yard, next to the prairie I have instead of a lawn. I counted at least four different kinds of bees. I saw dancing whites, painted ladies, and black swallowtail butterflies (no monarchs on that particular day, but there have been a few already this season). I saw the first hummingbird moth of the year. I noticed that the coneflowers are blooming.

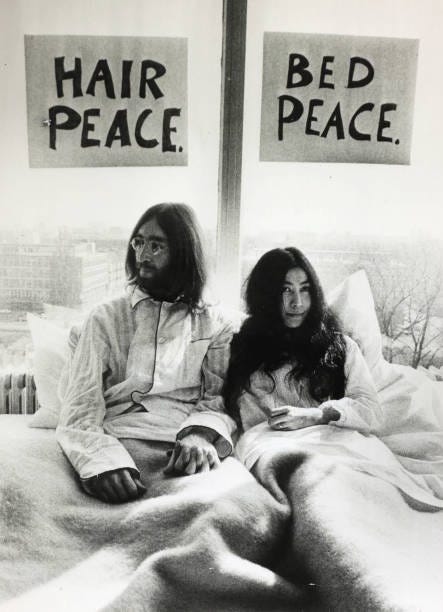

Sometimes resistance looks like millions of people in the streets. Sometimes it looks like a body at rest in a garden. Or in a bed. Or a cafeteria. Or on the ground. Bodies in motion are powerful. So are bodies that are still. The world needs both, and while some people can do a lot, no one can do everything. It took me a long time and a lot of pain to learn that, but now I’m proud to do what I can, and grateful that you’re doing what you can do, too, whatever that looks like.

Is your body part of the resistance? What does that look like for you? Would you ever participate in a bed-in? How about a prairie protest? Maybe I’ll make myself a sign for the next one, and invite some extra soft friends to join me.

One final question: where is your hope coming from these days? Please share in the comments. Shared hope is compounded hope.

*worth noting that I almost completely broke down afterward and spent six months on the couch watching Jerry Springer studying for the GRE.

**Honestly, I still haven’t been able to completely let go of it. Even though I know it’s unnecessary, even though I know these beliefs don’t serve anyone, even able-bodied folks, I still wish I could do “more.” Maybe I always will. But now I know why I feel that way, and I can direct my energy into changing the narrative of worth—or hold myself with gentle compassion on days when that feels too difficult.

***First off, shout out to the (Extra) Softies! Your support means the world. Still, I can only do this work because my partner has skills that are highly valued by society and is able to support our entire family. I am aware that this makes me enormously privileged. In the book Unfit Parent, author Jessica Slice reports that as of 2023, the disability income for those who were unable to work full-time before becoming disabled (so, me) is $10,900 per year [67]. Not only that, “benefits cease if a disabled person saves more than $2,000” [71].

Disability Pride is resistance. Keep resisting.