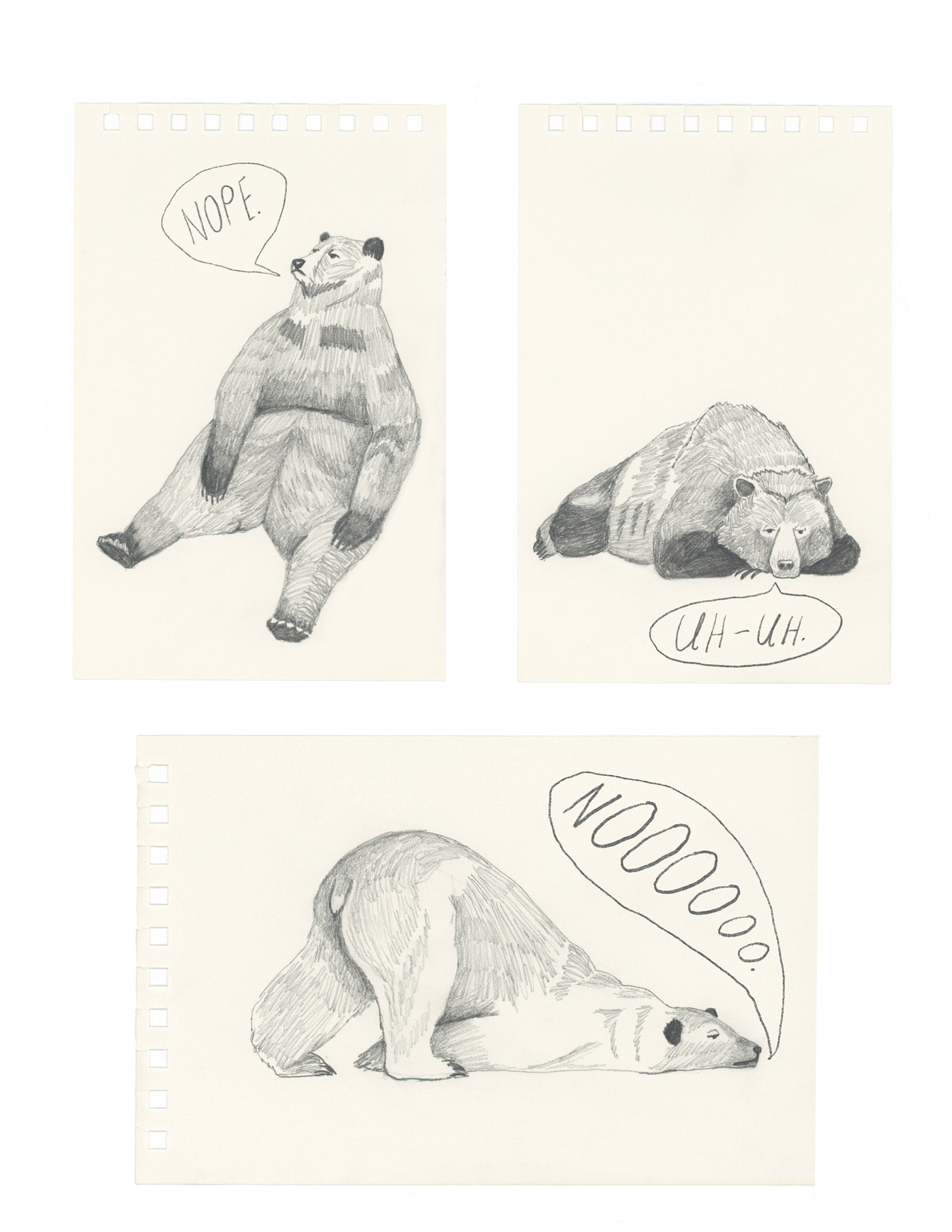

Mama Bear

a metaphor/allegory/emotional memoir/absolutely true tale of being a chronically ill, disabled parent

Once upon a time there was a woman-type person who found herself in middle age. She had always considered herself to be kind of on top of things. Sort of. Mostly. Actually, now that she thought about it, she wasn’t sure. Had she always been this scattered? This forgetful? This tired? She was having a hard time remembering. Her mind felt heavy, lumbering and slow. Her body did, too.

Oh girl, same, the other moms said. Between the pandemic, the children, the perimenopause, the state of the world. But they were still doing Pilates and working their jobs and getting their kids to enrichment activities. They could still drink coffee, and wine, and eat chocolate. The woman-type person found herself increasingly unable to tolerate much more than blueberries and salmon. So healthy! the other moms said. I wish I had your willpower. She felt an overwhelming urge to rake her nails across their faces.

Her doctor suggested hormone therapy. Light therapy. Therapy-therapy. But she was already doing all that and more. She found herself drifting off in conversations. Staring silently, blankly, after someone asked a question. Words were leaving her, she thought. Feelings, though, were still there. Anger, jealousy, frustration, longing, love. If anything, the feelings were louder, sharper than they’d ever been. It bothered her, at first, not to be able to wrap all those feelings up in words. I don’t think I know how to be a human, anymore, she told her spouse. Nobody does, he said. Thankfully, eventually, she ran out of the energy to care.

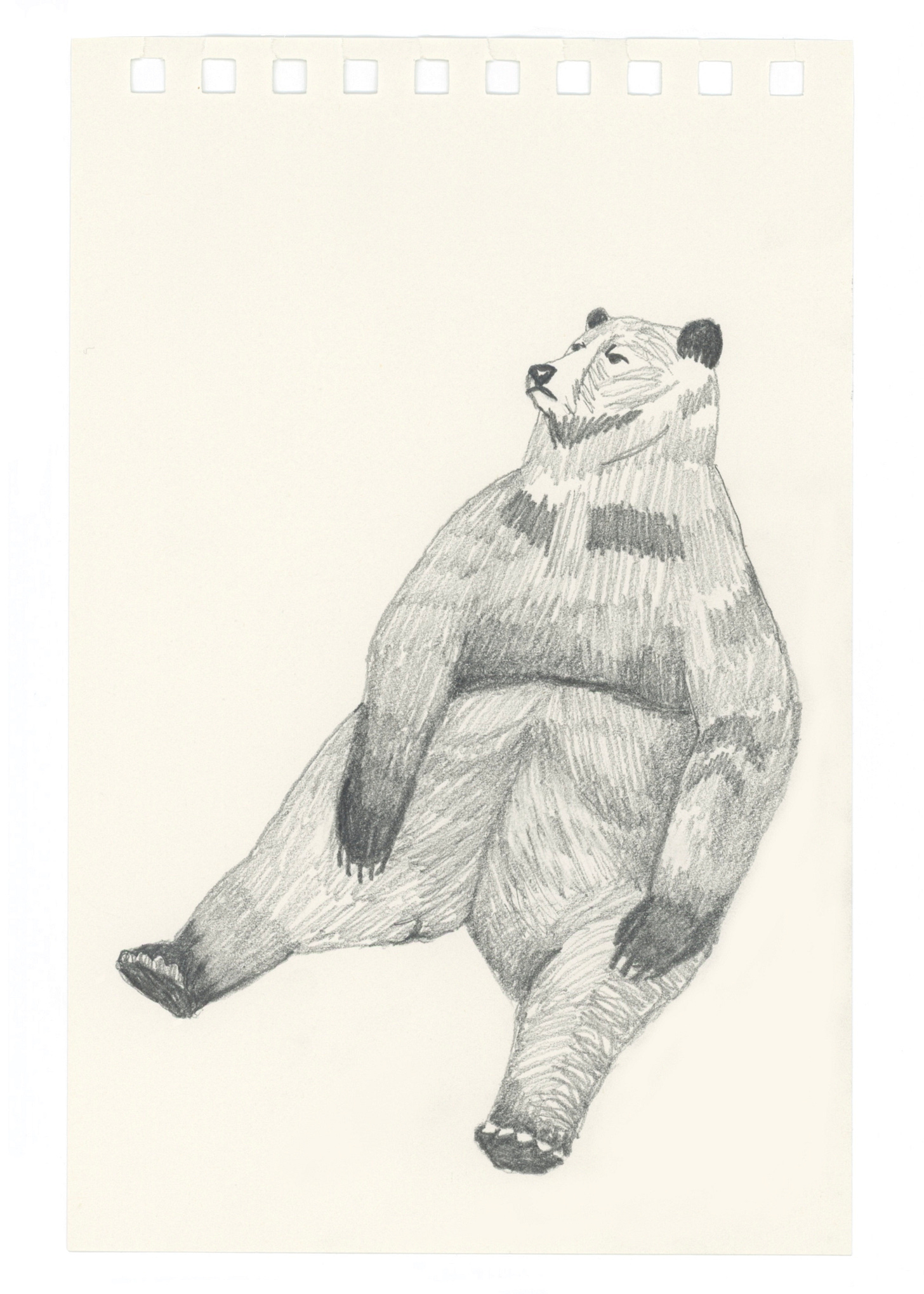

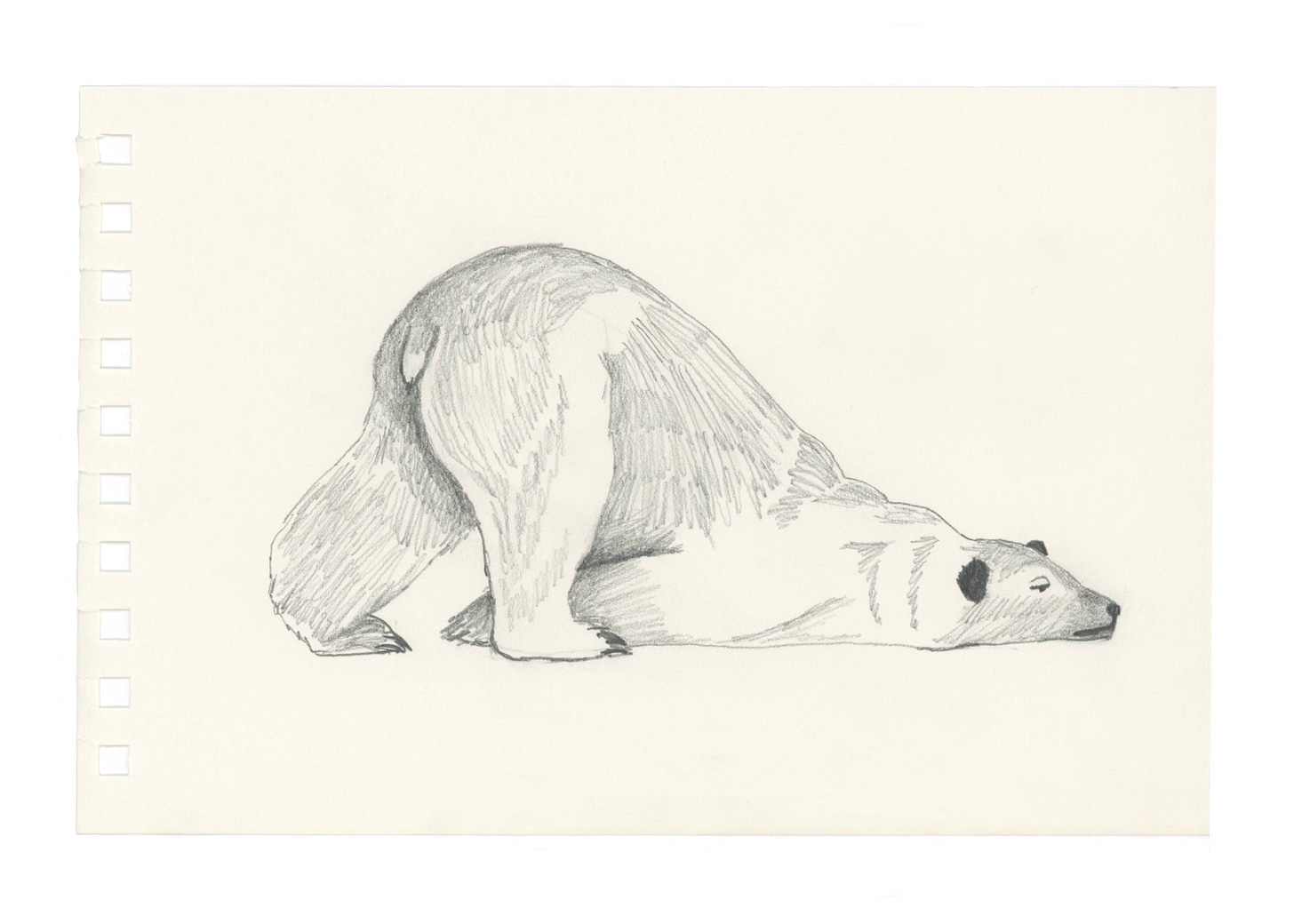

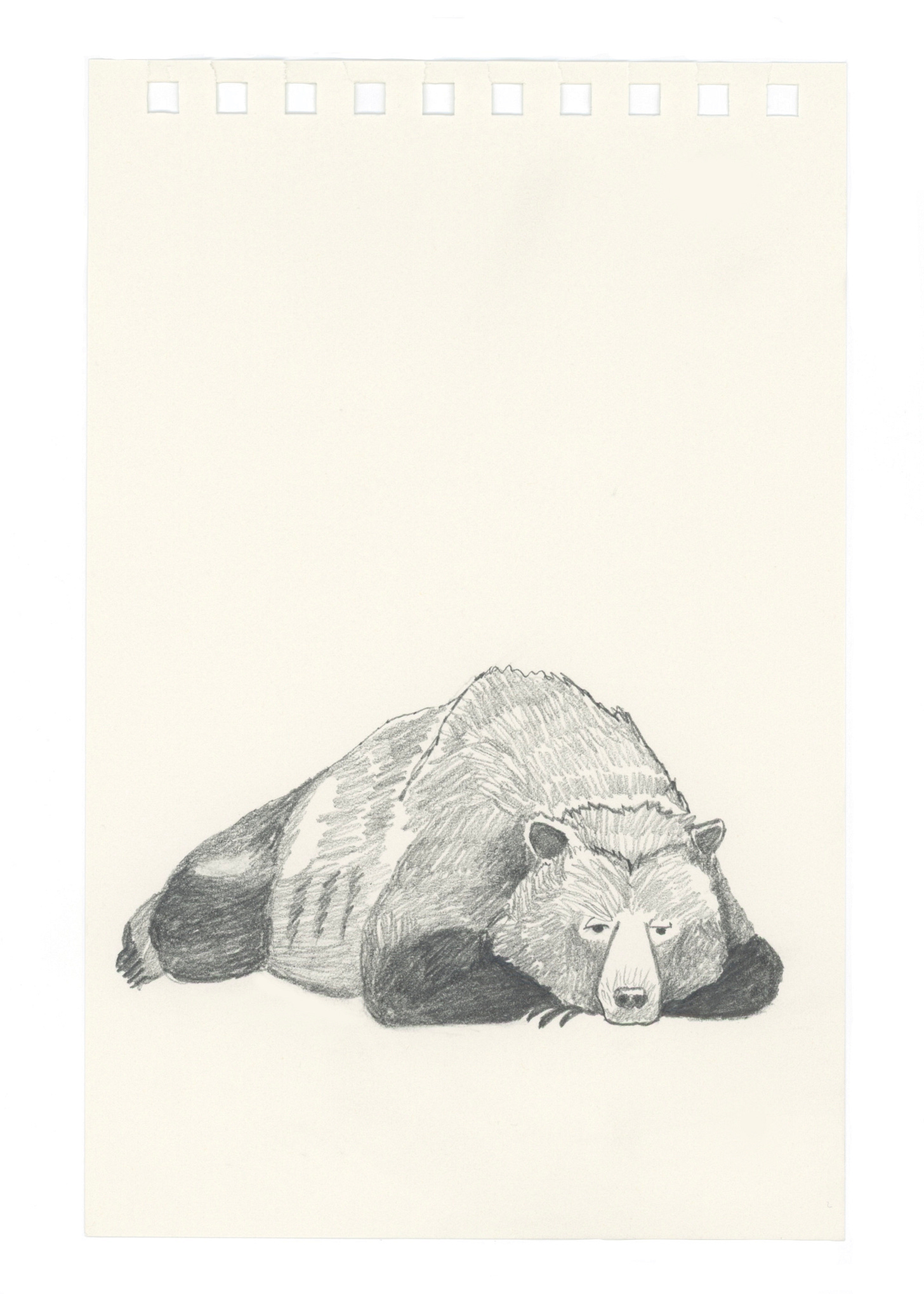

She took to her bed at the end of November, one of those afternoons when the sun set during school pickup and midnight-dark coated the windows before dinner. When her children tried to wake her, she growled. After that, her spouse directed the kids to steer clear of the bedroom. All through the winter, he made their breakfasts and lunches and took them to school. All through the winter, the thick hair that had always covered the woman’s legs grew thicker, spread onto her torso and down her arms. The wood of the bed frame groaned beneath her gathering weight. She dreamed of clear streams and damp earth. The smell of pine and cedar, the crunch of needles and leaves under her bare feet.

When she awoke in the spring she was ravenous. She stumbled down the stairs. Her family had piled the table with blueberries and salmon, and she devoured it all. At first the children flinched when she pulled them to her, but she was careful with her claws, and the pads of her paws were soft. She breathed in the sweet tang of their scalps and felt her heart stretch open. The children laughed—her breath, so much stronger now, so much warmer, tickled. She got down on the floor and let them crawl onto her back, which was broader and stronger than it had ever been. They clutched fistfuls of her fur, but it didn’t hurt. For the first time in years, nothing hurt. She craned her giant head backward and licked the children’s faces.

She couldn’t make their breakfasts or lunches, but she carried them to school: dangling by the backs of their jackets in her mouth when they were younger, riding on her back once they’d grown. She didn’t understand their words, but she knew when they were scared or sad, and she nuzzled their salty tears, held them close to her wooly chest until they fell asleep. She couldn’t help them with homework, or drive them to sports practices, but she could roar on the sidelines, and sit beside them while they worked, her huge heart beating love love love.

In the beginning she wondered if a day would come when no one would need her anymore. She longed for it sometimes, back then, her mouth clamped on the collars of tiny coats. She imagined finally loping off into the forest, alone. She still dreamed of the forest; a place of soft moss and warm meat. A place she had never been. A place she knew, now, that she would never go. Because even when her children left and started lives of their own, even if her spouse moved away, or fell in love with a human, or died, her soft animal body belonged with the people she loved. The people she needed. Just as much as, if not more than, anyone needed her. It was a relief to keep her body near them all. It was a relief to be, and to be loved, just as she was.

*

Lately I’ve been feeling like I’m not very good at being a person. I’m starting to think, though, that it’s not so much being a person, and more being this person[1]. My body and my life have changed so much over the past few years. I’m still trying to figure out how to be who I am now. Sometimes I think it would be easier if I were a bear.

How are you at humaning these days? Would you rather be an animal? If so, which one? Would you still be my friend if I became a bear? I don’t actually like salmon all that much, but I do eat blueberries every day.

[1] Truthfully I’m not sure that I’ve ever been good at humaning, but before I was disabled I sure was good at pretending.

I adore this! First, lots of gentle hugs, because man. But also, oh, and those BEARS.

I would wear one on a t-shirt, not going to lie. <3

this felt soothing to read. beautiful. relatable.

i used to think i was bad at being human, i thought that for the majority of my life. but in recent years i think i’m doing fine at being a disabled human–the thing i’m not good at is capitalism. which is unfortunate when you live in capitalism 😂 but it’s a kinder thought and that saves me some energy.

if i were an animal i would like to be a spoiled housecat. they’ve got it made lol.